Six handshakes away

Have you ever heard about “six degrees of separation”? It’s about the famous idea that there are always less than about six persons between two individuals chosen at random in a population. Given enough people, you’ll always find someone whose uncle’s colleague has a friend that knows your nextdoor neighbour.

Fun fact: it’s where the name of the long-forgotten social network sixdegrees.com came from.

Mathematically, it checks out. If you have 10 friends and each of those friends has 10 friends, in theory that’s a total of 1+10+9*10=101 individuals. In practice, when you have 10 friends, they probably know each other as well, and their friends most probably do too. You end up with way fewer than 101 people, and no two persons in your “social graph” ever end up more than one or two handshakes away from each other.

In graph theory, those kinds of graphs where you have densely connected communities, linked together by “hubs”, i.e. high-degree nodes, are called “small-world networks”.

Oh you know Bob? Isn’t it a small world!

I learned about it a few weeks ago in a very nice (French) video on the subject, and immediately thought “I wonder what the graph of everyone I know looks like”. Obviously, I can’t exhaustively list every single person I’ve met in my life and put them on a graph.

Or can I?

One of the few good things™ Facebook gave us is a really fast access to petabytes of data about people we know, and especially our relationships with them. I can open up my childhood best friend’s profile page and see everyone he’s “friends” with, and click on a random person and see who they’re friends with, et cætera. So I started looking for the documentation for Facebook’s public API which, obviously, exists and allows for looking up this kind of information. I quickly learned that the exact API I was looking for didn’t exist anymore, and all of the “alternative” options (Web scrapers) I found were either partially or completely broken.

So I opened up PyCharm and started working on my own scraper, that would simply open up Facebook in a Chromium Webdriver instance, and fetch data using ugly XPath queries.

1

2

def query(tab):

return "//span[text() = '" + tab + "']/ancestor::div[contains(@style, 'border-radius: max(0px, min(8px, ((100vw')]/div[1]/div[3]/div"

After 180 lines and some testing, I had something that worked.

Basically, the script loads a Facebook account’s friends list page and scrolls to the bottom, waiting for the list to dynamically load until the end, and then fetches all the links in a specific <div> which each conveniently contain the ID of the friend. It then adds all of those IDs to the stored graph, and iterates through them and repeats the whole process. It’s a BFS (breadth-first-search) over webpages.

In the past few years, a lot of people started realizing just how much stuff they were giving away publicly on their Facebook profile, and consequently made great use of the privacy settings that allow, for example, restricting who can see your friends list. A small step for man, but a giant leap in breaking my scraper. People with a private friends list appear on the graph as leaves, i.e. nodes that only have one neighbour. I ignore those nodes while processing the graph.

It stores the relationships as adjacency lists in a huge JSON file (74 MiB as I’m writing), which are then converted to GEXF using NetworkX.

Now in possession of a real graph, I can fire up Gephi and start analyzing stuff.

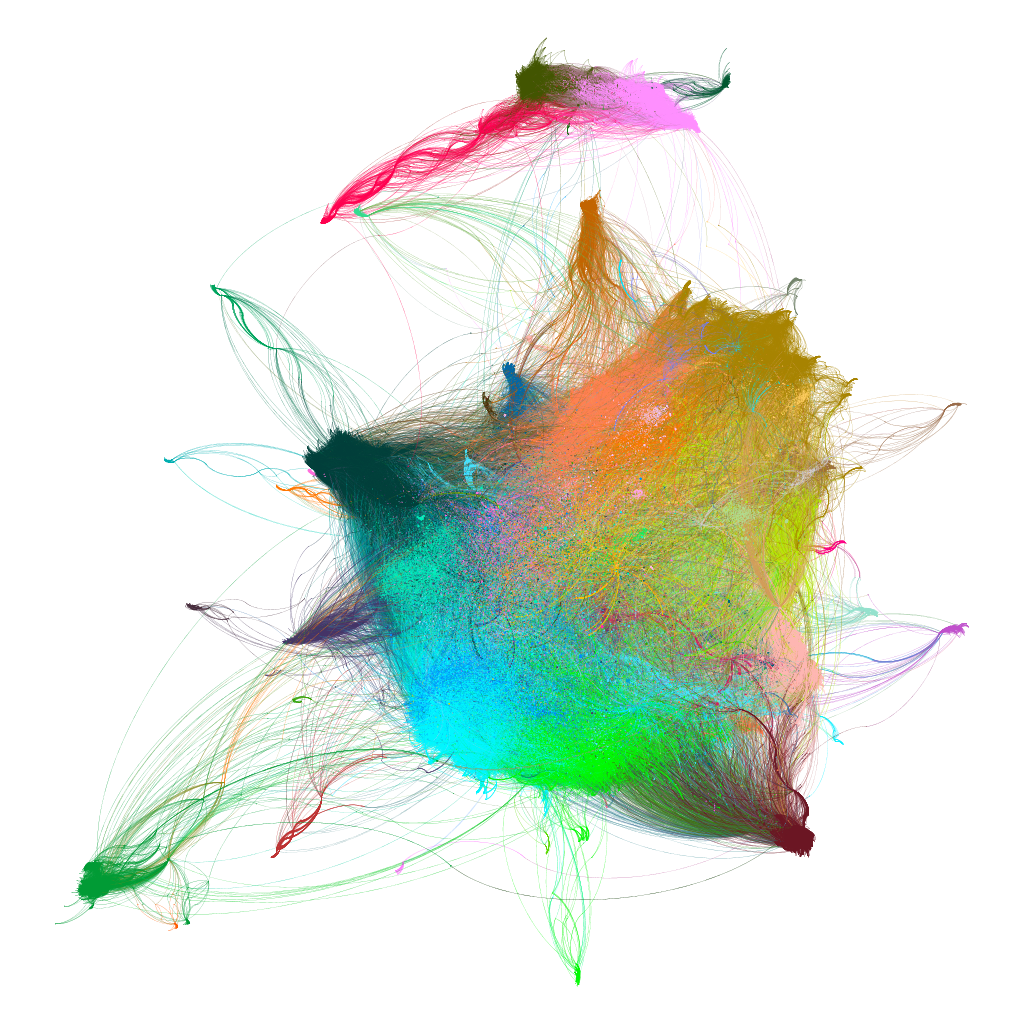

The graph you’re seeing contains around 1 million nodes, each node corresponding to a Facebook account and each edge meaning two accounts are friends. The nodes and edges are colored according to their modularity class (fancy name for the virtual “community” or “cluster” they belong to), which was computed automatically using equally fancy graph-theoretical algorithms.

At 1 million nodes, the time necessary to layout the graph and compute the useful measurements is about 60 hours (most of which is spent on calculating the centrality for each node) on my 4th-gen i7 machine.

About those small-world networks. One of their most remarkable properties is that the average length of the shortest path between two nodes chosen at random grows proportionally to the logarithm of the total number of nodes. In other words, even with huge graphs, you’ll usually get unexpectedly short paths between nodes.

But what does that mean in practice? On this graph, there are people from dozens of different places where I’ve lived, studied, worked. Despite that, my dad living near Switzerland is only three handshakes away from my colleagues in the other side of the country.

More formally, the above graph has a diameter of 7. That means that there are no two nodes on the graph that are more than 6 “online handshakes” away from each other.

In the figure above, we can see the cumulative distribution of degrees on the graph. For a given number N, the curve shows us how many individuals have N or more friends. Intuitively, the curve is monotonically decreasing, because as N gets bigger and bigger, there are less and less people having that many friends. On the other hand, almost everyone has at least 1 friend.

You’ll maybe notice a steep hill at the end, around N=5000. This is due to the fact that 5000 is the maximum number of friends you can have on Facebook; so you’ll get many people with a number of friends very close to it simply because they’ve “filled up” their friends list.

We can enumerate all pairs of individuals on the graph and compute the length of the shortest path between the two, which gives the following figure:

In this graph, the average distance between individuals is 3.3, which is slightly lower than the one found in the Facebook paper (4.7). This can be explained by the fact that the researchers had access to the entire Facebook database whereas I only have access to the graph I obtained through scraping.