Running a Windows executable on Linux in 17 easy steps

What a time to be alive. GNU/NT is not a fever dream anymore, people actually play games on Linux, and—famously—the Windows ABI is actually the only stable ABI for Linux. Really, it’s something to behold. Microsoft is actually shipping their own Linux distribution (yes, that Microsoft).

The landscape really is different from what we had twenty years ago. Rumour has it that even audio works on Linux now.

Captain, it’s Wednesday

There’s still one Big Problem plaguing basically every developer that wants to do cross-platform work: the modern computer is three (eh… say two and a half) heavily different operating systems fighting each other for market share.

| OS | Userland | (binary) Backwards compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | 410 COM interfaces under a trenchcoat | As long as Raymond Chen’s happy |

| macOS | Whichever Objective-C clone the cool kids are using | Until the next CPU architecture change |

| Linux | Basically UNIX | Just recompile |

The most common “porting paths” nowadays are:

- run Linux things on Windows

- this is mostly a solved problem with WSL1 and WSL2

- run Windows things on anything else

- this is hard

There isn’t a huge amount of overlap between “people using Mac software” and “people tech-savvy enough to try to run those on something else than a Mac”, so I won’t focus on that now. Life always finds a way, though.

The first path is pretty straightforward. Linux is really not that big of an API surface. Doing pretty much anything you’d expect an OS to do requires installing third-party software. Linux is a kernel and doesn’t try to be anything more. Hence, implementing syscalls, /proc, and /sys already gets you pretty close to a real Linux system. If your code’s correct, compile a compositor and a window manager and you’ve got a working desktop Linux environment.

There are rough edges, of course. Implementing proper hardware support is hard, especially if you’re building on top of another OS, like WSL1 did. Which is why they scrapped¹ it and made WSL2.

¹ They “have no plans to deprecate WSL 1” but still manage to break it in an RTM build.

Windows has the opposite philosophy. It’s batteries-included. This means that if you try to open it and see what’s inside, it will catch fire and burn you.

Windows includes a kernel (NT), a graphics stack (actually, part of it is in the kernel), an audio stack, a network manager, an update system, even a Prolog interpreter (well, it used to. All good things must come to an end). It’s more comparable to a Linux distribution than to Linux itself. Making a compatibility layer for Windows is, thus, more akin to making a compatibility layer for one specific Linux distribution (with its specific window manager, libc version, package manager, …).

Running Windows apps is an enormous undertaking. You need to implement all those components (or many apps won’t work). And then you need to make sure that all of these work together, because they’re all tightly coupled, from decades of wizardry and performance hacks (or apps will work weirdly). Again, imagine having to implement not just Linux, but X11/Wayland, GNOME/KDE/…, PulseAudio, NetworkManager.

The Problem

There’s a famous tool in the Skyrim modding community called Cathedral Assets Optimizer (CAO). Its exact purpose is outside the scope of this article, but to put it simply one of its important features is converting files between formats used by Skyrim LE (Legacy Edition, the old 32-bit one) and those used by Skyrim SE (Special Edition, the new 64-bit one). It’s a Windows-only tool, because, well, Skyrim runs on Windows.

One of those formats is the .hkx file format. Skyrim uses the Havok physics engine, and the .hkx format is a binary format mainly used for storing animations. Havok being the industry-grade optimized beast that it is, the format has a specific version for 32-bit and for 64-bit, each taking the maximum advantage of the platform’s capabilities. A 32-bit .hkx file thus can’t be loaded from a game using Havok 64-bit, and vice versa.

The problem has been reduced to a simple sentence: how to convert 32-bit .hkx files to 64-bit? (and vice versa)

There exists a file called HavokBehaviorPostProcess.exe that ships with Skyrim SE and does exactly what we want: convert 32-bit files to 64-bit. It’s a standalone executable (doesn’t require any DLLs except for the system ones and MSVC). Really, it’s a nice EXE file. Does its job, doesn’t make my life hard. I’ve renamed it to hkx32to64.exe here for readability.

1

2

> hkx32to64.exe LE_INPUT.hkx

error: success

So, CAO uses this tool to allow users to convert their files. Everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

Except for one thing: the author of CAO (check out his blog) is a friend of mine and he recently decided to port CAO to Linux. For the most part it was a smooth ride, since the GUI uses Qt (which is cross-platform), with the exception of some texture handling code that relied on DirectX to process DirectX-specific files, and the .hkx conversion code that relied… on running this hkx32to64.exe tool.

Without going into too much detail, assume the .hkx format is complicated enough that it’s not feasible to write a converter from scratch. People have tried before, people have tried writing specs, reverse-engineering the format, it’s excessively complicated. Reverse-engineering that EXE file is also out of the question, it’s optimized code, there’s bits of C++ OOP craziness everywhere, I don’t want to subject anyone to that. Neither IDA nor Ghidra are useful here. So we’ll just go along with the assumption that we need to actually use this tool.

So, we need to find a way to make this .hkx conversion feature work on Linux.

Bringing Out the Big Guns

A simple CLI tool? That’s really the easiest thing to run on Linux. No complicated dependencies, no installation weirdness. Just use Wine.

1

2

$ wine hkx32to64.exe LE_INPUT.hkx

error: success

Except when it doesn’t. First, it’s a 32-bit EXE file, which means you need 32-bit Wine. There’s an old bug on Debian and Ubuntu that sometimes prevents wine32 and CUDA from being installed at the same time. Wine depends on ocl-icd-libopencl1 (which provides libOpenCl.so), but CUDA depends on nvidia-opencl-icd (which… also provides libOpenCl.so). Obviously, apt won’t let you install two packages that provide the same file (what would happen if you were to uninstall one of them?), so if you try to install wine32 while CUDA is installed… it will uninstall CUDA. Learned that the hard way.

So, to recap, my friend would have to tell users to uninstall CUDA if they want to use CAO on some of the most used Linux distributions. Not ideal.

Or use Nix. But hey, who am I to judge?

Wine is already in itself a pretty big requirement (takes a bit more than one gig of disk space once installed).

Ideally we’d wanna find another way.

Settling for Reasonably Sized Guns

What’s an EXE file, really? Just a bunch of instructions for the CPU to execute. Especially if all it does is reading from a file, doing some processing on it, and writing that back to another file.

We should be able to do something like:

1

2

char* buffer = read_file_content("hkx32to64.exe");

goto *buffer;

This is actually syntactically correct C code if you’re using GCC. There’s nothing wrong about jumping to an address in memory (except for the security hole of jumping to an address in memory). You’re doing it all the time anyway when using ifs and loops.

The code, however, will not work, because an EXE file doesn’t contain only code. It’s a complex format, that contains multiple segments of data: code, global variables, debug information, among others.

If the binary file were a flat binary (i.e. a file that contains only code, no segments, no headers), such as DOS’s COM files, then, it could work. Some adjustments would have to be made to mark the memory area as executable since most modern OSes prevent executing code from non-text segments, but… it would work. Don’t do it, though. Please.

Hello from the Other Side

A program can’t do anything without calling the OS it’s running on. This is the very basis of how programs work nowadays: the OS is there to define the resources the program can access and to make sure the program doesn’t do anything bad. You can’t write in memory without the OS giving you a memory area to write in, it’s not the DOS days anymore. So, OSes provide a bunch of functions that programs can call to do things: these functions are syscalls.

Most OSes do, anyway. There are weird OSes that don’t.

Here’s an example on Linux amd64:

1

exit(123);

1

2

3

mov rax, 60 ; exit syscall number

mov rdi, 123 ; exit code

syscall ; call the kernel

Note that I specified Linux and amd64. Each kernel has its own list of syscalls, and each architecture has a way (sometimes more) for a userland program to call the kernel. On amd64, parameters are put in registers and the syscall instruction calls the kernel. On Linux i386, it’s int 0x80. On DOS, it was usually int 0x21.

Most Unix-like kernels keep a stable syscall interface, for a simple reason: historically, they haven’t had direct control over their standard library (i.e. libc, usually). On Linux, you’re probably using glibc, but that’s because Linus settled on the GNU userland a while ago, nowadays you could very well be using musl, or uClibc, or dietlibc, or any other libc, really. How does the libc do things? By calling syscalls.

Here’s a simple way to implement exit for Linux amd64 in C: (we’ll forget about threads and exit_group for now, it’s just an example)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void exit(int code)

{

asm volatile(

"mov $60, %%rax\n"

"mov %0, %%rdi\n"

"syscall\n"

:

: "r"(code)

: "rax", "rdi"

);

}

The asm instruction is not portable C and the syntax to emit assembly code from C code will vary depending on which compiler you’re using. But the method is correct: the exit syscall will always be 60 on Linux amd64, and the parameter will always be passed in rdi. This function, although limited to Linux amd64, is correct and will still work in 10 years (on Linux amd64).

I could easily change that bit of code to make it work on Linux i386. However, Windows and macOS have a different way of doing things. Both also have syscalls, that are called using the same mechanism, but the list of syscalls and numbers associated to them is not stable and regularly changes. Tracking the syscall changes between NT releases takes a huge amount of effort and is generally not relevant anyway for application developers. macOS syscalls are a bit easier to list since XNU is open-source but there’s still no stability guarantee.

On Windows and macOS, it’s expected that you never use anything lower level than the OS’s standard library to do OS-related things. On Windows, this is a bunch of DLL files, on macOS, it’s Framework bundles (inherited from NeXTSTEP) and .dylib files.

Shameless Plug

If our EXE file only calls the OS through functions from the standard library, then we just have to plug ourselves in the middle. Really, this is what Wine does. When you run an EXE through Wine, it gets loaded in memory, and then Wine puts the addresses of its own functions where the program expects to find the addresses of the Windows APIs it’s using. Wine does it for everything because its goal is to be able to run everything. We just want to run hkx32to64.exe.

If only there was an easy way to load .EXE files and inject code in them…

We’ll be using code from this nice repository by Tavis Ormandy. Quoting the README:

This repository contains a library that allows native Linux programs to load and call functions from a Windows DLL.

A Windows DLL… we’re trying to run an EXE file. Plot twist: an EXE file is a DLL file. Both are PE files containing code. An EXE file is designed to be ran independently while a DLL is designed to be loaded by a running application, but they’re the same format. Even Windows’s native LoadLibrary function supports loading EXE files.

This is what we’ll be doing here: loading hkx32to64.exe and simply running its entrypoint (its main / WinMain function).

Friends Made Along the Way

The repository contains a proof-of-concept example of running Windows Defender, and as such contains enough bits of the Windows API to handle that specific executable. Obviously, a lot of those APIs won’t be used by our EXE file, and conversely our EXE file probably uses APIs that Windows Defender doesn’t.

Luckily, the PE loader used here properly handles unresolved imports: it tells us in the console what function was missing. We just need to try to run the EXE file, see what’s missing, and implement the missing functions. Eventually, we’ll also be able to try removing the unused functions, but it’s not essential for our purpose.

For example, here’s an execution of hkx32to64 that fails because of a missing function:

1

2

3

$ ./hkx32to64 LE_INPUT.hkx

hkx32to64: function at 0x66ca17 attempted to call an unknown symbol

Trace/breakpoint trap

Hm. This doesn’t really tell us exactly what function was missing. Indeed, here’s the bit of code in loadlibrary that displays this error message:

1

2

3

4

5

void unknown_symbol_stub(void)

{

warnx("function at %p attempted to call an unknown symbol", __builtin_return_address(0));

__debugbreak();

}

This unknown_symbol_stub function is what’s written when the linker can’t find an imported function. We could simply make the linker display an error whenever that happens, but then we’d have a problem: it’s quite common for an EXE file to import functions it never uses. We don’t want to implement every single one of those functions, we just want to implement exactly what is needed to convert our .hkx files.

So, the address it prints is actually the return address. As a reminder, here’s what a function call looks like in assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

0000 call myfunction

0005 mov eax, 123

...

myfunction:

0123 mov eax, 456

0128 ret

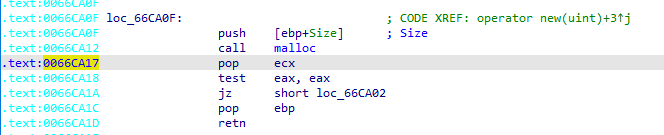

call foobar is a shortcut for push <address immediately afterwards> and jmp foobar. ret is a shortcut for pop <address>, jmp <address>. Indeed, when calling a function, all the callee needs is the address to return to. Not the address that called it. So, here, __builtin_return_address(0) would return 0x5, which is the address of the mov eax, 123 instruction. There are many ways to call a function in x86 assembly, but we’ll assume that call <name> was used, since it’s the most common one. It’s a 5-byte instruction, with a 1-byte opcode and 4-byte operand. That operand is what we’re looking for, so if the return address is $x$, the address of the instruction that called the function is $x - 5$. Here, it’ll be 0x66ca12. Let’s see what’s at that address:

1

2

$ xxd -s 0x66ca12 -l 5 engine/hkx32to64.exe

0066ca12: 4d30 5130 57 M0Q0W

Uh… that’s just some hex numbers. We’re reading assembly code, so let’s use a disassembler:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ objdump -D --start-address=0x66ca12 engine/hkx32to64.exe | head -10

engine/hkx32to64.exe: file format pei-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

0066ca12 <.text+0x26ba12>:

66ca12: e8 0d 10 00 00 call 0x66da24

66ca17: 59 pop %ecx

66ca18: 85 c0 test %eax,%eax

Okay, that’s already better. We’re calling 0x66da24. What’s 0x66da24?

1

2

$ objdump -D --start-address=0x66da24 engine/hkx32to64.exe | tail +8 | head -1

66da24: ff 25 a8 01 77 00 jmp *0x7701a8

So it’s reading the address at 0x7701a8 and jumping to that. There’s actually nothing in the EXE file at that address, because that address is in the .idata section, which is precisely the section where the loader writes the addresses of imported functions during the dynamic linking process. We’ll need to look at the EXE file’s import table for that. 0x7701a8 is an absolute address in the process memory, but the import table stores RVAs (Relative Virtual Addresses), which are relative to the executable’s base address. On Windows, it’s usually 0x400000, but we can check that in the PE header:

1

2

$ objdump -p engine/hkx32to64.exe | grep ImageBase

ImageBase 00400000

So, taking that into account, the address we’re looking for is $\texttt{7701a8}_{16} - \texttt{400000}_{16} = \texttt{3701a8}_{16}$. Let’s see what import section 0x3701a8 belongs to, by finding the section that contains it:

1

2

$ llvm-readobj-11 --coff-imports engine/hkx32to64.exe | grep -oP 'ImportAddressTableRVA: 0x\K.+' | sort -r | awk '$0 <= "3701A8" { print; exit }'

3701A8

Okay, so it’s in section 0x3701a8, and it’s the first item of the section. Let’s see what’s in that section:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

$ llvm-readobj-11 --coff-imports engine/hkx32to64.exe | sed -n '/3701A8/,/}/p'

ImportAddressTableRVA: 0x3701A8

Symbol: malloc (25)

Symbol: _aligned_malloc (1)

Symbol: _aligned_free (0)

Symbol: _set_new_mode (22)

Symbol: free (24)

Symbol: _callnewh (8)

}

Eureka! The function that was called is malloc.

We’ll just add it to the list of functions used by the loader:

1

DECLARE_CRT_EXPORT("malloc", malloc); // we can just use libc's malloc

Phew, that was a lot of work just to determine what function was called. Next time, I’ll just use a full EXE disassembler that handles imports, such as IDA:

(but then, I wouldn’t be a true Unix hacker™)

It would have been nicer if the unknown_symbol_stub function had printed the name of the function instead of its address. It’s actually quite hard: unknown_symbol_stub is stored as a pointer, because… that’s how functions are dynamically called, at the lowest level. We can’t store data in a function pointer. Or can we?

The Magic of Retrofitting Things on a 50-Year-Old Language

A function that stores data is a called a closure. This is what we want here: store the missing function name along with the missing symbol stub function.

C doesn’t support closures, and actually, I don’t know of any languages that supports them that would allow you to pass a closure as a function pointer and just call it. It’s really not a good idea.

We’re gonna do it anyway (using the “thunk” method). I won’t go into detail of the inner workings of that approach. It’s horrifying enough to use it.

Here’s the stub now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

void unknown_symbol_stub_inner(char* name)

{

warnx("function at %p attempted to call an unknown symbol '%s'", __builtin_return_address(1), name);

__debugbreak();

}

void (*unknown_symbol_stub_builder(char* name))() {

return make_thunk(name, unknown_symbol_stub_inner);

}

...

if (get_export(symname, &adr) < 0) {

ERROR("unknown symbol: %s:%s", dll, symname);

address_tbl[i] = (ULONG) unknown_symbol_stub_builder(symname); // <--

continue;

}

Let’s rerun hkx32to64 with a missing malloc:

1

2

3

$ ./hkx32to64 LE_INPUT.hkx

hkx32to64: function at 0x65e5f6 attempted to call an unknown symbol 'malloc'

Trace/breakpoint trap

That’s better!

We only want to use that workaround during development, though. Each of those closures is an unnecessary allocation that we never free afterwards.

Implementing Windows

Now that we have a nice workflow for implementing missing functions, well, let’s implement them. There were quite a few that I had to grab from Wine’s implementation of the MSVC runtime, especially for the floating-point routines.

A lot were left empty or returned constants, enough to make the EXE happy, like these:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

STATIC unsigned int CDECL ___lc_codepage_func()

{

return 1252;

}

STATIC CDECL int _initialize_narrow_environment(void)

{

return 0;

}

STATIC CDECL int _configure_narrow_argv(int mode) {

l_debug("%d", mode);

return 0;

}

I had to do some weird things to fix the I/O features: hkx32to64 uses the <iostream> header, which is a part of the C++ standard, but I don’t want to meddle with C++ things, so when the programs asks for std::cout or its friends, I just give it the matching C streams:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

STATIC FILE* CDECL __acrt_iob_func(unsigned index)

{

switch (index)

{

case 0: return stdin;

case 1: return stdout;

case 2: return stderr;

default: return NULL;

}

}

DECLARE_CRT_EXPORT("?cout@std@@3V?$basic_ostream@DU?$char_traits@D@std@@@1@A", stdout);

DECLARE_CRT_EXPORT("?cerr@std@@3V?$basic_ostream@DU?$char_traits@D@std@@@1@A", stderr);

Those long names full of fancy characters are the mangled names of the C++ symbols. The C world relies on the same name always referencing the same thing, but in C++, things can be overloaded, and templated. C++ symbols, when exported, are internally renamed to long strings encoding type information and other stuff to allow the compiler to make sure it’s the exact thing we’re referencing. This is why you need to put your C++ code in

extern "C"blocks when you want to use it from C code.

Then, in my implementation of the stream methods, I just call the C I/O methods:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

// operator<<(ostream& os, const char* s)

FILE* stream_pipe_charptr(FILE* this, const char* str)

{

fprintf(this, "%s", str);

return this;

}

// probably the same but for std::string with small-string optimization

FILE* stream_pipe_charptr_len(FILE* this, const char* str, int len)

{

fprintf(this, "%.*s", len, str);

return this;

}

// std::endl

FILE* stream_endl(FILE* stream)

{

fputc('\n', stream);

return stream;

}

While writing this, I learned that

std::endlis actually a function. I thought it was some kind of magic object that would be replaced by a newline when the stream is flushed, but I’d actually never seen its exact signature or definition. Turns out, C++ streams allow piping a function looking likestream& fct(stream&), such thats << fctis equivalent tofct(s). That’s… weird, to say the least, but quite in line with the rest of the C++ streams API.

Note that the three above were embedded inside hkx32to64.exe by the compiler, because they’re templates (I think?). They’re not imported from the MSVC DLLs, so I’m just patching them directly in the process’s memory:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

struct {

DWORD address;

void* value;

} patches[] = {

{0x65cf90, stream_pipe_charptr},

{0x65d270, stream_pipe_charptr_len},

{0x65d410, stream_endl}

};

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(patches) / sizeof(patches[0]); i++) {

BYTE* addr = (BYTE*)patches[i].address;

void* value = patches[i].value;

// replace the first instruction in the function to patch by `JMP value`

// which is encoded as E9 DD CC BB AA

// with E9 being the opcode for `JMP rel32`

// and 0xAABBCCDD being the relative jump offset

// i.e. the distance from the next instruction and the jump target

// so, destination - source - sizeof(JMP rel32)

// with sizeof(JMP rel32) being 5 bytes

addr[0] = 0xe9;

*(DWORD*)(addr + 1) = (DWORD)value - (DWORD)addr - 5;

}

Okay, all the functions are implemented, let’s give it a go:

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ ./hkx32to64 LE_INPUT.hkx

error: success

$ md5sum OUTFILE64.hkx OUTFILE64.hkx.reference

aa8eb3f95c6d2237738a90c1629fed97 OUTFILE64.hkx

aa8eb3f95c6d2237738a90c1629fed97 OUTFILE64.hkx.reference

It works, and the output file matches the one we got when running the EXE on Windows!

The resulting ELF binary (which only contains the PE loader code and the Windows API bits) is 1 megabyte. That’s not small, but it’s nothing compared to a full Wine installation’s 1 and a half gigs.

Removing unused Windows API functions gets us down to 817 kilobytes.

Conclusion

Before this project, I’d never have thought that it would be that “easy” to run an EXE file on Linux without Wine. Like, I knew how PE files worked, how a dynamic linker worked, how Wine worked, but it just didn’t cross my mind that all it would take to run an EXE file would be… an afternoon of implementing missing functions.

Of course, again, this is a very simple program. Porting a GUI app would already be multiple orders of magnitude harder, since you’d have to implement Windows GUI APIs. Here, I only had to add wrappers for the C runtime and a few I/O functions, and to copy-paste some code from the Wine codebase.

Tavis Ormandy’s library is a welcome addition to my toolbox; I’ll probably use it again in the future if I need to use old DLL files for which the source is not / hasn’t ever been available.

A fun project overall.

A few followup questions:

- how hard would it be to do the opposite — load Linux ELF libraries from Windows programs, by hooking standard library functions? specifically not by implementing raw syscalls like WSL1 does

- can WSL1 be used for that? like, is there a way (even undocumented) to

dlopenLinux libraries from a normal (non-picoprocess) Windows process through WSL1?

And a few followup projects:

- retrowin32 by Evan Martin: an emulator for Windows binaries that runs in the browser. Really interesting