Using AWT in C#, and other funky things

A story of how Microsoft ported Java to .NET and accidentally created Windows Forms in the process, only to throw it away and pretend it never happened.

If you don’t care about the “History” part, you can skip directly to the technical part.

A bit of history

In the late 90s, Microsoft started working on a development platform supposed to replace COM, which was back then an absolute behemoth in the world of Windows programming: everything new was being built on top of COM. Office? That’s OLE, just COM with more spaz. VB6? Just COM libraries. New Windows components all got their own shiny COM interfaces. It worked so well even Apple used it (a bit).

That said, writing in C or C++ was still a pain, and VB6 still had some kind of “toy language” connotation to it – sure, it was good, second to only Delphi in terms of fast GUI development (“RAD”), but it was still far from what Sun had been offering for a few years with their amazing new “Java” platform. It lacked true OOP, and tended to become hard to maintain for large projects.

Java, you say? That “write once, run anywhere” thing? That’s a problem for Microsoft. If I can run my corporate app anywhere, why would I pay for a Windows license?

Microsoft, deep down, was born as a development tools company. Sure, they ended up buying IP here and there and sold an operating system to IBM in the 80s, but they still started by selling BASIC interpreters for 8-bit CPUs.

The most important part of an operating system is the ecosystem. People want to use their computers to do stuff, and for that they need apps, and these apps need to have been written by someone. If it’s hard to write apps for your platform, developers will flee to the competition and your platform will die.

Except, of course, if you know your platform will succeed, and developers know it too. The most famous example of a hard-to-write-software-for platform for which a lot of software got written is Sony’s PlayStation 3. Its CPU, however powerful it was, was all but idiosyncratic. It was really hard to write efficient code for it, but game developers still did it, because it was the PS3.

Operating systems have some kind of inherent inertia. Computers are shipped with an OS, and the vast majority of people either don’t want to use another OS or simply don’t know that they can, and they end up just using whatever’s installed out of the box, and for most personal computers, even back then, that’s Windows. Then, once you’ve spent a few years getting comfortable with that, when it’s time to upgrade you tend to choose the next version of the same OS, because that’s what you’re most familiar with. Meanwhile, software developers wrote their software in the hope of selling it, so it’s in their advantage to write it for well-known OSes. And having software available for one OS is an incentive for people to use it. Getting the world to change their OS is hard, because you have a dozen virtuous circles to break.

Hard, but not impossible. If people start writing their software in a language that works everywhere, then that’s less and less of an incentive to stay on whatever OS you’re using. Java, in the 90s, was a threat to Microsoft and Windows’s monopoly on business computing.

Redmond fights back: Visual J++ and MSJVM

Microsoft’s first attempt to counter Sun was in the form of Visual J++, which was nothing more than a licensed implementation of Java and the JVM. It ended with Sun suing Microsoft about it and the whole product was litigated out of existence because it was not compliant enough with the Java specs, so Sun forbid Microsoft from selling anything with the name “Java” on it.

J++ had something that Java was missing, however: the ability to use the Win32 APIs in a clean, object-oriented, managed way. These APIs were exposed under the name “Windows Foundation Classes”, which should remind you of the “Microsoft Foundation Classes”, the well-known C++ library-set/framework for writing Windows apps.

The year is 1996, and this is real code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

import com.ms.wfc.app.*;

import com.ms.wfc.core.*;

import com.ms.wfc.ui.*;

public class HelloWorld extends Form

{

public HelloWorld()

{

super();

setText("Hello World");

setAutoScaleBaseSize(new Point(5, 13));

setClientSize(new Point(292, 266));

MessageBox::show("Hello World", "Hello World");

}

public static void main(String args[])

{

Application.run(new HelloWorld());

}

}

If it looks like Windows Forms… it’s because it is. Or rather, it will be, in a few years.

In parallel, what would later become .NET was still brewing. The VB development team had been working for some time on something called the “Common Object Runtime”. It walked like COM and quacked like COM, but it was really object-oriented, and had proper garbage collection. Later, this would become the CLR, or “Common Language Runtime”. The original name (“COR”) persists in the name of one of the main assemblies used in .NET today, mscorlib.dll.

On top of that runtime, a language was being developed. It was internally called “Cool” (even though Microsoft denied it), and it was a statically-typed, object-oriented language with a C-like syntax. If that sounds suspiciously like Java, that’s because it pretty much was. Anders Hejlsberg, who’d previously worked on Object Pascal at Borland, and was one of the main designers of aforementioned J++ and WFC, was the lead architect of “Cool”. He’s good at making languages and stuff.

I won’t go too much in the details of .NET and C# themselves, because it’s not the topic, and this chapter is already way too long.

Giving up in style: Visual J#

After Microsoft was forced by Sun to stop using Java, they had a problem: sure, .NET sold, and C# was nice, but for a lot of Java users it wasn’t enough to warrant a switch. They needed a way to get Java developers to use .NET, and they needed it fast.

And fast they got it: in October of 2001, the first beta version of Visual J# (codenamed “Banjara”) was uploaded to MSDN. Webloggers of the time were quick to check it out.

There they had it: Java, running on the CLR. You wrote regular-ass Java code and it would get compiled to CIL code and run on the CLR virtual machine, effortlessly referencing other CLR assemblies written in C# or VB.NET.

This lasted for a few years, until Microsoft deprecated it around 2007-08 and now you’d be hard-pressed to find anything referencing it. There are still bits of documentation lying around on MSDN, but apart from that, your best bet is archive.org.

There is a caveat: J# targets .NET, which includes the .NET standard library. Java has its own standard library – System.out.println has to come from somewhere. Which means… J# includes its own implementation of the Java standard library APIs. As CLR assemblies.

Microsoft also released a bytecode converter that could translate JVM bytecode from Java class files to MSIL/CIL bytecode, so in theory you could take your existing compiled Java code and run it on .NET through the J# runtime.

Let’s use Java from C#

Under the right conditions (.NET Framework, no .NET Core), if you reference the vjslib.dll assembly from the Visual J# files, the following C# code works:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

java.lang.System.@out.println("Hello World");

}

}

Obviously, it also works in VB:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Module Module1

Sub Main()

java.lang.System.out.println("Hello World")

End Sub

End Module

J#’s language support is frozen to Java 1.1.4, so don’t expect fancy features. Most notably, there are no generics, so it’s just ArrayLists all over the place. However, Java 1.1 already had AWT, and Microsoft actually provided an AWT implementation in J#! This means we can do this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

using java.awt;

using java.awt.@event;

class Program

{

class Handler : WindowAdapter

{

public override void windowClosing(WindowEvent evt)

{

java.lang.System.exit(0);

}

}

class ButtonDemo : Frame

{

public ButtonDemo()

{

var b1 = new Button("OK");

var b2 = new Button("CANCEL");

this.setLayout(null);

b1.setBounds(100, 100, 80, 40);

b2.setBounds(200, 100, 80, 40);

this.add(b1);

this.add(b2);

this.setVisible(true);

this.setSize(300, 300);

this.setTitle("button");

this.addWindowListener(new Handler());

}

}

static void Main()

{

new ButtonDemo();

}

}

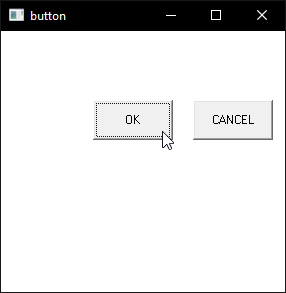

Running it gives us this:

Getting to the point

When I first saw this, I was quite impressed. Implementing the JDK on top of .NET, that’s quite a feat. But can it do more than run a 20-line example?

I took an old school project of mine, a 2048 game I wrote while in second year of college, that used AWT and other JDK features, and tried to… port it to C#. I started by simply copying and pasting all the code, replacing extends and implements with :, boolean with bool, event to @event, and so on. Java and C# really are similar in terms of syntax, most differences are only superficial. C# doesn’t have anonymous classes though, so that gave me a bit of trouble for all event handlers, but hey, you can’t have your coffee and drink it too.

Here’s a bit of code highlighting a few differences between the original Java code and the result in Frankenstein-J#-C#:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

GameCanvas(Frame parent, Game2048 model)

{

/* ... */

addMouseMotionListener(new MouseMotionAdapter()

{

@Override

public void mouseMoved(MouseEvent e)

{

super.mouseMoved(e);

for (GameCanvasButton btn : buttons)

{

btn.setButtonInfo(e, false);

}

}

});

/* ... */

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

public class mousemotion : MouseMotionAdapter

{

private GameCanvas canvas;

public mousemotion(GameCanvas canvas)

{

this.canvas = canvas;

}

public override void mouseMoved(MouseEvent e)

{

base.mouseMoved(e);

foreach (GameCanvasButton btn in canvas.buttons)

{

btn.setButtonInfo(e, false);

}

}

}

public GameCanvas(Frame parent, Game2048 model)

{

/* ... */

addMouseMotionListener(new mousemotion(this));

/* ... */

}

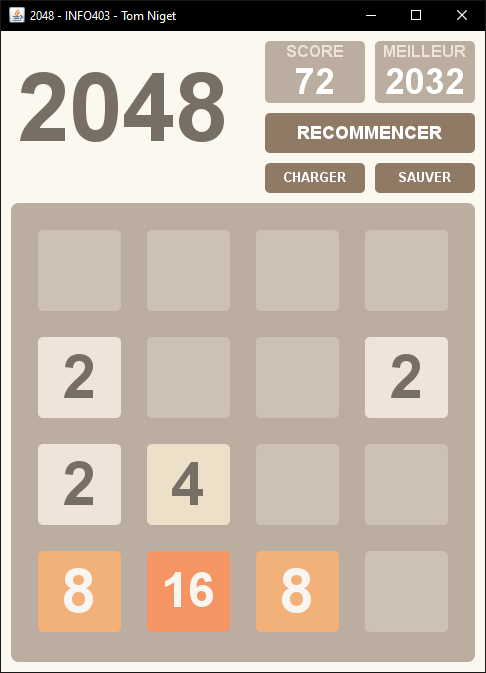

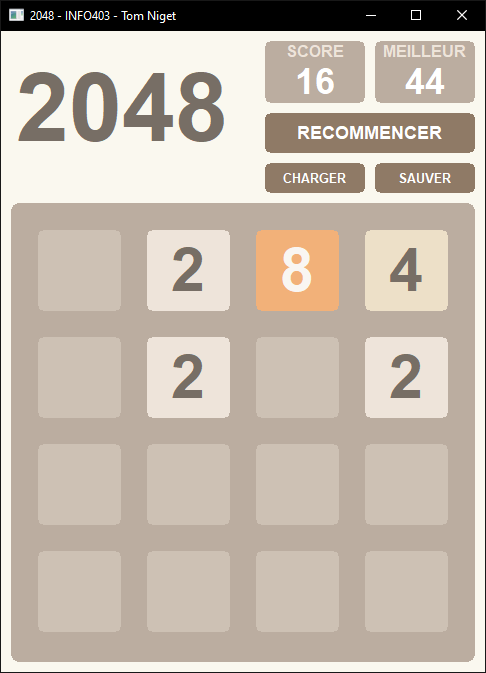

And here’s what both versions look like:

The AWT-on-.NET version is slightly different from the original Java one. The most glaring difference is the quality of the text antialiasing which is noticeably worse on the Microsoft implementation. The Java version uses grayscale antialiasing, while the .NET one uses subpixel, but for some reason it doesn’t work well. Also, the rounded corners on the buttons are not smooth on the .NET version. Apart from that, well, it works perfectly well.

The source code for the game is available here in Java and here in C#.

A quick peek under the hood

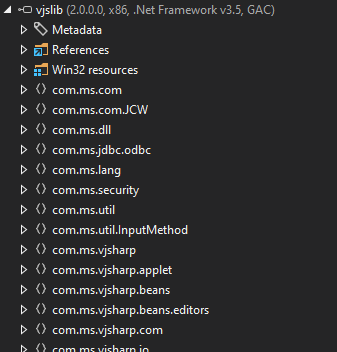

.NET assemblies are really easy to decompile, there are lots of free tools that can disassemble CIL to pretty readable C# code. I used JetBrains’ dotPeek for this.

It’s really funny seeing Java things in the .NET universe. Let’s have a look at the java.lang.Boolean class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

namespace java.lang

{

[JavaInterfaces("2;java/io/Serializable;System/IConvertible;")]

[Serializable]

public sealed class Boolean : Serializable, IConvertible

{

private const long serialVersionUID = 3497507091445339353;

public static readonly Class TYPE;

public static readonly Boolean TRUE;

public static readonly Boolean FALSE;

private bool __value;

public Boolean(bool val) => this.__value = val;

public Boolean(string str)

{

if (str == null)

this.__value = false;

else

this.__value = string.Compare(str, VJSlibConsts.getString(715), true, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture) == 0;

}

public virtual bool booleanValue() => this.__value;

public override bool Equals(object obj) => obj != null && obj is Boolean && ((Boolean) obj).__value == this.__value;

public static bool getBoolean(string name) => Boolean.valueOf(java.lang.System.getProperty(name)).booleanValue();

/* snip */

[JavaFlags(4227077)]

[JavaThrownExceptions("1;java/lang/CloneNotSupportedException;")]

public new virtual object MemberwiseClone()

{

Boolean boolean = this;

ObjectImpl.clone((object) boolean);

return ((object) boolean).MemberwiseClone();

}

}

}

This is the decompiled code for the Boolean class, with a few bits removed for brevity.

There’s a really weird mix of things here. The [Serializable] at the top is .NET’s System.SerializableAttribute class, while the : Serializable bit is Java’s java.io.Serializable interface.

There are Java methods (such as booleanValue) following the Java naming conventions (camelCase), and .NET methods (such as Equals) following the .NET naming conventions (PascalCase).

We can also see that an attribute is used to store Java’s checked exceptions information for the MemberwiseClone method: [JavaThrownExceptions("1;java/lang/CloneNotSupportedException;")] is the equivalent of throws CloneNotSupportedException in Java.

Another Java feature that’s missing from the C# language actually does exist in .NET and is used in J#’s JDK: the synchronized keyword which locks on the object’s monitor:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

namespace java.util

{

[JavaInterfaces("3;System/ICloneable;java/util/List;java/io/Serializable;")]

[Serializable]

public class Vector : AbstractList, ICloneable, List, Serializable

{

/* snip */

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.Synchronized)]

public override bool add(object e)

{

this.addElement(e);

return true;

}

/* snip */

}

}

Visual J# 2005 can be downloaded from archive.org.